The Kandy Perahera

by M.D. Raghavan, Ethnologist Emeritus,

National Museums of Ceylon

In the religious and social life of Ceylon

there is nothing more resplendent than the annual Kandy

perahera pageant. By tradition, a celebration commemorating the victory of the

Devas against the Asuras, on the day after the new moon in the month of Esala,

it possibly began as a celebration sacred to Maha Vishnu, the Lord of Sri

Lanka. A festival of the Gods, it was later incorporated with the festival of

the sacred Tooth Relic.

The Kap Inauguration

|

Wanakku Rala Herath delivers the kap to an official of Kataragama Devale |

The annual Kandy Esala Perahera is inaugurated

with the planting of the kap at the four devales of Natha, Maha Vishnu,

Kataragama and Pattini on the day following the new moon in Esala. An Esala

tree (the Indian Laburnum—Cassia Fistula) in full bloom at this time of

the year, is supposed to be cut and its stem planted as the kap at the

four devales. It has in modern times been replaced by a jak tree (Atocarpus Integrifolia)

cut into four sections, one for each of the four devales. A drum tattoo

from the Naha devala announces the ceremonial conveyance of the

stumps to each of the devales.

Reaching the devale, the kap is duly

planted at the allotted place in the premises facing east. For the next four

days the devale perahera is conducted within the devale premises. Following

this first stage, the perahera goes in procession for ten days in succession

over a prescribed route along the main streets of Kandy.

On each of these days, the peraheras of the devales proceed to the entrance to

the Dalada Maligawa, where they join the Maligawa perahera and the combined

procession goes winding along the prescribed route.

The Two Phases

The first six days of the perahera, is called the Kumbal

Perahera, and the second phase of the perahera, the Randoli Perahera, from the randoli

or the gilded palanquins of the four devales, which are a feature of the

processions the next five nights. To the average visitor the religious side of

the perahera scarcely impresses as much as the spectacular side of it. On all

these days the vast precincts facing the Dalada Maligawa is a scene bustling

with excitement, alive with dancers in several stages of bedecking themselves

with the costumes and jingles that lend colour and resonance to the perahera

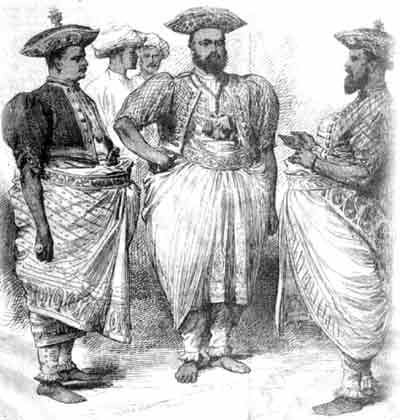

pageant. The great man behind the perahera is the Diyawadana Nilame in a resplendent

costume of an embroidered tunic and shining silk, of some twenty yards wrapped

round his waist with a head gear of a four cornered golden coronet.

The Progress of the Procession

To the visitor who comes to see the Perahera, for

the first time, it is an exciting event. Expectantly and patiently he waits at

a point of vantage commanding a good view of the procession. Faint sounds of

the flourishing of whips are the first indication that the procession is

approaching and the perahera bursts to view, with the whip crackers standing in

a ring wielding enormous snaky whips. The whip crackers herald the perahera.

The component parts of the procession open out in their proper order and the

perahera spreads out in all its stateliness, to the brilliant illumination of

hundreds of torches.

The Diyawadane Nilame and the three Basnayake Nilames of

the devales and the Kandyan chiefs walk in the procession in measured steps

and slow with all pomp and dignity. At intervals in majestic stateliness come

the elephants in colourful trappings, the Dalada Maligawa tusker leading and

bearing aloft the sacred relics in a gorgeously bedecked ransivige, the

golden howdah brilliantly lit with electric jets, the cynosure of all eyes.

Kandyan dancers in brilliant array, delight the

beholders with their impressive performance of Kandyan dancing. Folk plays, Li-Keli

and Kalagedi malai add to the variety and charm of the

procession which in all its pomp and orderliness proceeds over the appointed

route of the main streets of Kandy.

The Water-Cutting

On the last night of the

Randoli Perahera, the procession after going round the city,

separates itself into two parts. The Maligawa part proceeds to Adhana Maluwa Gedige

Vihare where the golden karanduwa containing the sacred relics, is

deposited. The Devale peraheras proceed to their respective

Devales, and before dawn proceed to Getambe Tota for the Diya Kapana Mangallaya,

"the water-cutting" ceremony. Reaching the Mahaweli Ganga, the procession

halts. The Kapuralas and the functionaries of the Devales row up the river in

decorated boats. Reaching the middle of the river, the kapuralas with a golden

sword describe a circle in the waters. Each throws out the water taken at the

previous year's "water-cutting" ceremony, and dips the golden kendiya

taking fresh water.

The ceremony over, the procession returns to the Ganadevi

Kovila for the performance of a series of customary ceremonies. Proceeding from

the Ganadevi Kovila, the devale peraheras join the Dalada Maligawa perahera

returning from the Adhana Maluwa in the afternoon. This, the Day Perahera,

proceeds thrice round the temple square. The devale peraheras

return to their respective devales towards the evening, and the Maligawa

perahera to the Maligawa. This concludes the Kandy Esala Perahera.

Kandy Perahera: The Historical Background

A link with the

past, the Kandy Perahera reflects the glory of the days that are no more, the

days of the pomp and splendour of the Kandyan

monarchy when the King personally directed the arrangements for the great

event. It then served the further purpose of a royal levee, at which were

present the two Adigars, (Governors of Provinces) and

all the other chiefs. The King took his stand at the Octagon of the Dalada Maligawa—termed

the Pattiruppuwa, and presented himself

to the view of his assembled subjects in the square below, who eagerly awaited

a sight of his Royal Majesty.

The Adigars satisfied

the King as to the disposition of the several components of the long procession

each in its due order of precedence. The procession being duly formed and marshalled in the temple square, the King with all ceremony

brought the Karanduwa, or the relic casket containing

the Tooth Relic which he placed within the ransivige

on the howdah upon the Maligawa tusker.

The story of the

Kandy Esala Perahera runs con-current with the history of the Kandyan monarchy.

All Peraheras of Ceylon are annual celebrations of a devalaya

dedicated to one of the Gods. An additional sacredness of the Kandy Perahera is

its association with the Danta Dhatu,

the Tooth Relic. As the safety of the kingdom depended on the Tooth Relic, the

Perahera at the capital where the Tooth was enshrined,

received royal patronage.

The Kandyan King was the source of all pageantry and

pomp. Two of the main devales of Kandy, the Maha Vishnu

Devale and Naha Devale are regarded as built by King Narendra

Sinha (1707-1739). The subsequent Kings, Sri Vijaya Raja Sinha (173-9-1747), Kirti Sri Raja Sinha (1747-1780),

Sri Rajadhi Raja Sinha

(1780—1798) and Sri Wickrama Raja Sinha

(1798—1815) maintained the tradition.

All the Peraheras of

the Island follow the pattern of the Kandy Perahera, and

all Peraheras were continued to be held by the Kandyan Kings. At Kandy the responsibility

of conducting the Perahera was vested in the First and Second Adigars during the days of the Kandyan

Monarchy. Subsequently this became the responsibility of the Diyawadana Nilame

of the Dalada

Maligawa,

who dons the gorgeous dress of a Kandyan Chief with the distinctive head dress. The chief

official of a devale is termed the Basnayake Nilame

and such dignitaries at most of the devales of Ceylon are Kandyans. An interesting exception is the Basnayake Nilame

of the Dondra (Devundura)

devale, who though a Low-country Sinhalese, wears the costume of a Kandyan

Chief.

Kandy Sets the Pace

All the Peraheras

follow the pattern of procession of the Chief officers,

the elephants, drummers and dancers. Among the time-honoured

peraheras are those of Kandy, Gampola, Ratnapura, Dondra, Kotte, Alutnuwara, and Kataragama. For pageantry and magnificence

of display, the annual perahera of the Kotte Raja

Maha Vihare, comes close to the Kandy Perahera. No

perahera approaches the Kandy Perahera in the wealth of its picturesque

variety, its inordinate length, and its exuberance of dancers and folk-plays. Kotte having been an earlier Capital of the Kings, the

perahera there is indeed brilliant, next only to Kandy. The tradition at Kotte is one established by King Sri Parakramabahu

VI, who ascended the throne in 1415 A.D. Successive Kings respected and

maintained the tradition, even in the Kandyan period.

Queyroz, the eminent

Portuguese historian has left an account of the Kotte

Kings in his book "The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon" in

these words:

"This the ancient King of Kotte

signified by certain celebrated processions called peraheras, which lasted 16

days some being held by day and others at night, which amounted to thirty two,

and these by night were more famous. In them women took part with the same licence as in the Feast of Bacchus. The King used to go in

them with a bangle on one foot, made up of fifteen beads, which represents

those over whom he dominated."

|

| Photo courtesy: Lakpura Travels (Pvt) Ltd. |

De Queyroz has

over-drawn the picture of the place of the women dancers—who in the early and

late Middle Ages were a feature at all temple processions in South India and

Ceylon, and temples maintained families of dancers and musicians, who were

remunerated by lands held on service tenure.

Water-Cutting: A Ceremony in Sympathetic Magic

A ceremony often misunderstood or misinterpreted,

is the "water-cutting". The conception is erroneous that it is

symbolic of the parting of the waters of the Palk Strait with the magic

weapon of King Gaja Bahu (174–196 A.D.) when he crossed over on his South

Indian expedition. The water-cutting ceremony is indeed the most essential of

the ceremonials of the Perahera. At the ceremony, the water collected and

stored in the kendiya at the previous year's ceremony is poured out.

Plunging the vessel in the stream, fresh water is taken and preserved until the

next season. The Kapurala, the ritual priest, cleaves the water with a golden

sword, pours out the water, and replenishes the vessel with fresh water. The

splashing of waters, and the pouring out and refilling, are all part of the

symbolisms of the rain making ceremonies of the East, particularly of India.

"Water-cutting"

ceremony conceived in its proper perspective as symbolic of rain making, is an

illustration of sympathetic magical rites. In all lands where agriculture is

the mainstay of the peoples, altogether dependent on an adequate supply of

water, society and state have been at pains to seek divine aid for sufficient

rainfall.

From: Ceylon: A Pictorial Survey of the Peoples and Arts

by M. D. Raghavan, Ethnologist Emeritus,

National Museums of Ceylon

(Colombo: M.D. Gunasena & Co., Ltd.)

Chapter 18 (pp. 119-125)

|